2. The metallurgical analysis of the metal cauldrons

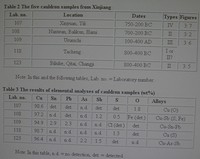

With the kind support of Xinjiang archaeologists, five samples taken from five different cauldrons were obtained. The dates and origins of these cauldrons are given in Table 2. The elemental analysis was also conducted on the polished sections in a scanning electron microscope (SEM) by using an energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence analyser (EDXA). It should be noted that what the EDXA analysis measures is actually the micro-composition that can only be taken as a general indication of the overall composition in a sample. Table 3 presents the results of elemental analyses of the five samples.

Table 3 shows that the four earlier cauldrons of Types I, II and IV (nos. 107, 108, 118 and 123) were made of copper with a small amount of minor elements such as As, Sb and S, while the only Type III cauldron of later date from Urumchi was of Cu-Sn-Pb alloy. The reason for using copper rather than tin bronze to cast cauldrons is not so clear but appears to be related to the availability of metal sources in the relevant localities. In this regard, it is worth noting that the two cauldrons containing 1-1.5% Sb (nos. 108 and 123) are from the areas close to each other along the northern foothills of the Tian Shan. This may hint at the availability of a local Sb-containing copper source in eastern Xinjiang. To clarify this issue further investigation is required.

As mentioned previously, the cauldron from Biliuhe with a pair of "three-legs" handles recalls similar pieces recovered in southern Siberia. This typological correspondence seems to be strengthened by the elemental analysis, because the alloy of Cu-As-Sb employed for manufacturing the Biliuhe cauldron was widely used in southern Siberia during the late first millennium BC, especially for fabricating belt plaques in animal styles (Devlet 1980: 32-33).

Intriguingly, the majority of cauldrons recovered in southern Siberia were also made of pure copper instead of tin bronze. According to Bogdanova-Berezobskaya (1963: 136, 153), among the twenty cauldrons analyzed, thirteen are pure copper, five arsenical copper (As 1- 1.5%), one tin bronze, and one Cu-Sn-Pb alloy. But in the cases of implements and weapons, such as knives, sickles, daggers and mirrors, tin bronze and arsenical copper were preferred to be employed as raw materials. It appears that copper rather than copper alloys were intentionally chosen for casting cauldrons in southern Siberia during the first millennium BC. But whether this is also true for Xinjiang needs further research.

On the surface of some cauldrons from Xinjiang, traces of the joint-lines of casting molds can be seen, indicating that they were cast by using piece-molds. It is well known that the piece-molds casting is a typical Chinese technology that was widely employed to cast thousands of ritual bronzes during the Shang and Zhou periods (17th-3rd centuries BC). So and Bunker (1995: 108) once published a cauldron with characteristic Chinese-style decoration as well as two-piece mold marks on the surface. They dated it to the 8th century BC and considered it as one of the earliest examples of its kind. Cauldrons with Chinese-style decoration but in smaller sizes were found also in Shanxi and Gansu provinces as well as in a museum collection in Japan (Wang Changqi 1989:7-10; Takahama 1997: 169). These examples seem to provide a clue for understanding the early stages of adopting piece-molds to the cauldron shape. So and Bunker (1995: 108) already suggests that 'the Chinese may have been among the first peoples to make the shape, which then traveled far into western Eurasia, becoming the signature article of the peoples in the Black Sea region'.

While the casting technology may have originated in northern China, the shape of cauldron may not necessarily be the same too. Chlenova (1994: 506) considers that the origin of the Scythian cauldrons goes back to those from Iran and partially from the Transcaucasian region and Asia Minor. Bunker (1997: 178) also considers that the cauldron shape and handles have no Chinese antecedents and traces the origins of the nomadic cauldron to Transcaucasia, where a cauldron made clearly in hammered metal was found. To get a better understanding of this issue, a comparative research is needed to bring together all cauldron finds from both eastern and western Eurasian steppes.

With regard to the cauldron shapes, it should be noted that the tripod cauldrons used by Saka people in the region of Semirechiye and Yili are quite similar in form to the three-legged "ding" vessels of the Shang and Zhou dynasties in the central plains of China (Bernshtam 1949: 351-2). This similarity may imply the presence of cultural influence from the east to Xinjiang and Semirechiye during the mid-first millennium BC (An 1996: 74).